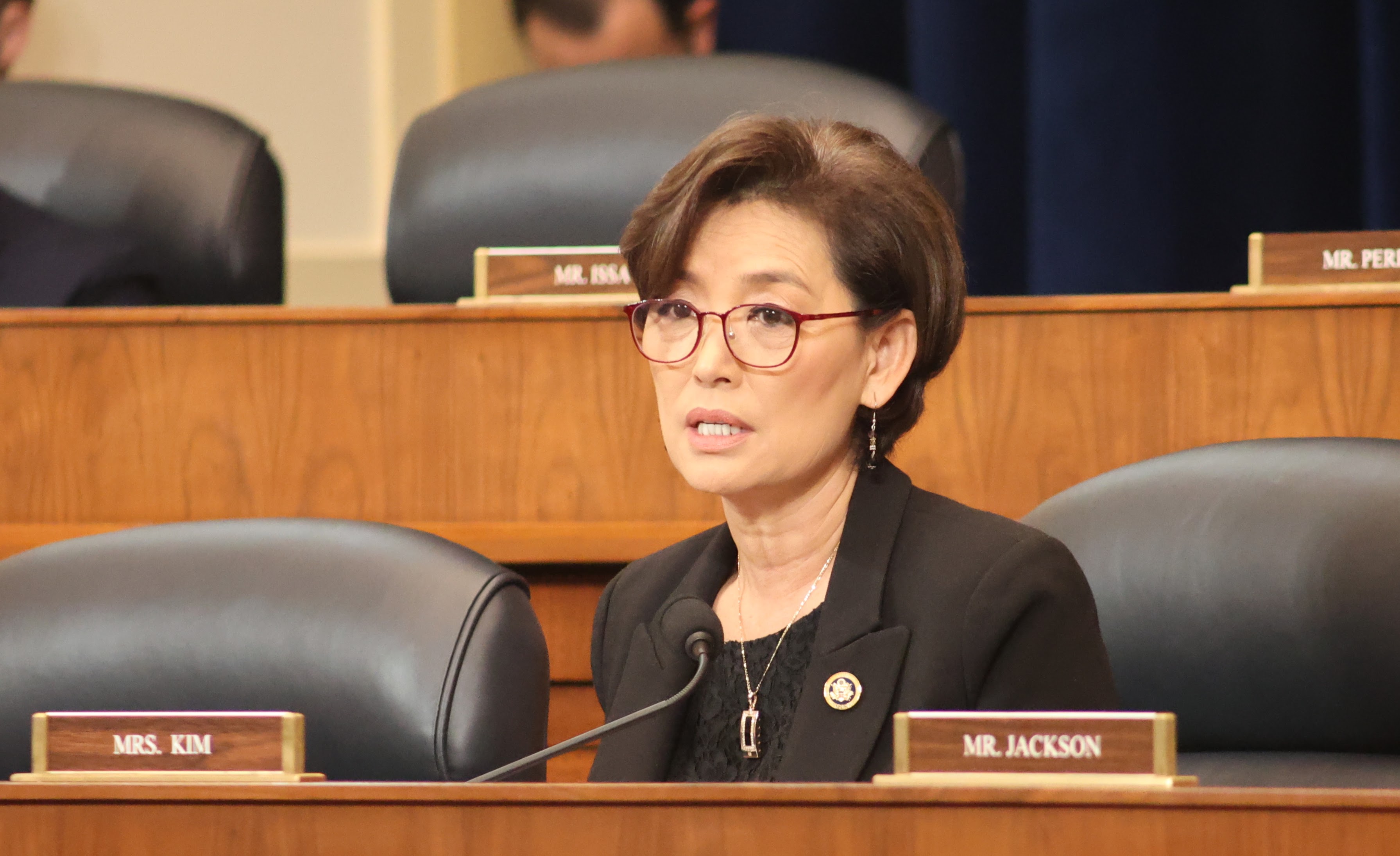

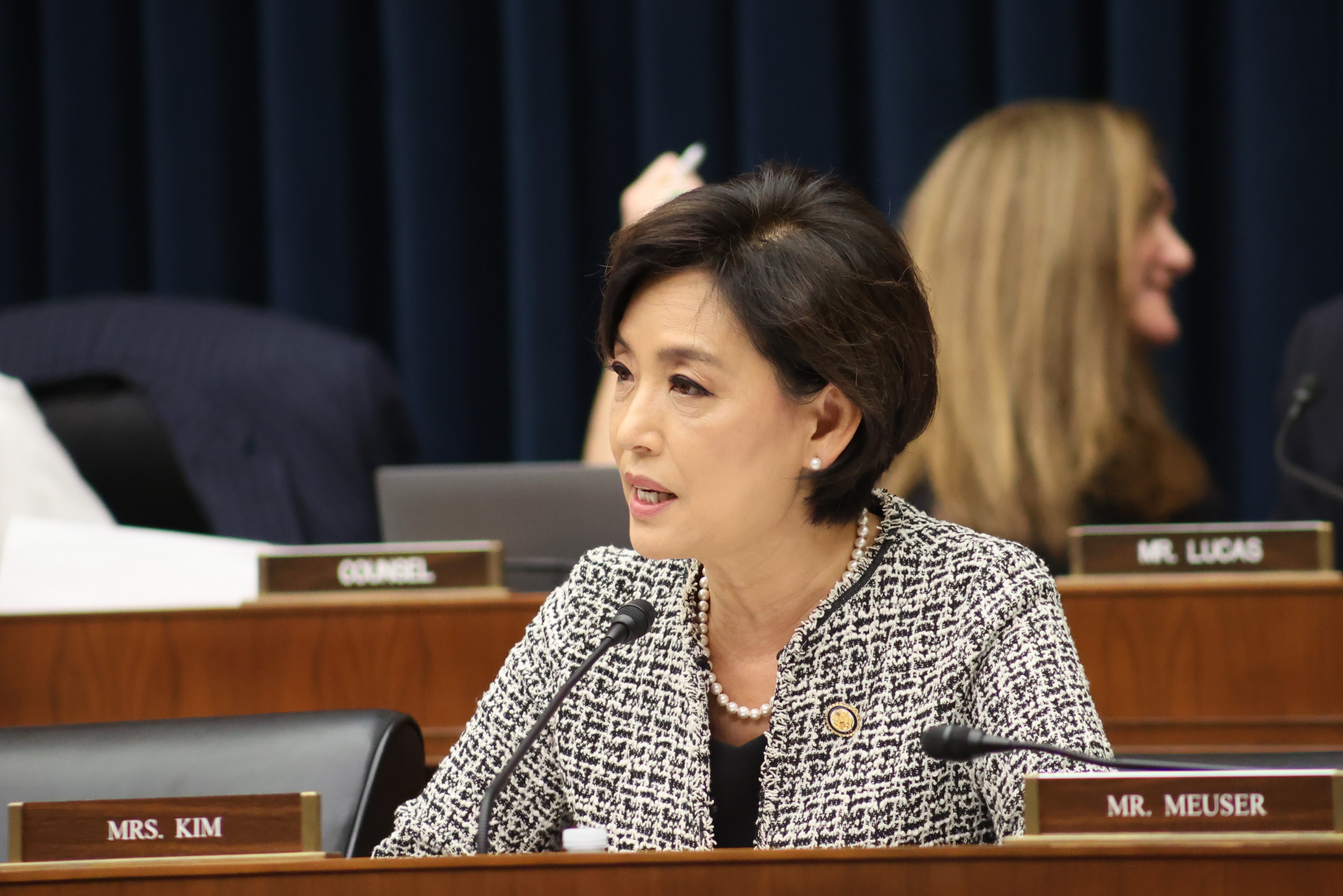

inutes before a mob stormed the House chamber last Wednesday, freshman Rep. Young Kim, a Republican from California, was on the phone talking about what it was like to be a new member of Congress.

“I look around and it’s pretty empty right now,” Kim said, describing her office in an interview. She talked about how she planned to make the office inviting to everyone, a microcosm of the melting pot that America is supposed to be. To Kim, the ability for anyone to influence the country’s trajectory is an important part of the American dream.

The ideal of the American dream seemed fragile throughout 2020, a year defined by economic turmoil and a disease that has disproportionately affected people of color and the poor. And after last week’s violence in the Capitol, it may seem like a relic of a past political age.

But newly elected GOP lawmakers from immigrant backgrounds have a unique perspective on the American ethos that could light a way forward for a party that has lost control of two branches of government and is facing a barrage of questions about who it represents.

Pull up the campaign websites of many of the Republican members of the freshman class, and you’ll see the phrase “American dream” again and again. Candidates of all stripes run on the platform of preserving it, but the idea is especially relevant to some new members of Congress. The group includes the first Iranian American ever elected to Congress and several other children of immigrants. Some members, like Kim, are immigrants themselves.

When she first arrived in the United States from South Korea after elementary school, Kim said, she often heard her parents talk about the life they hoped she would achieve.

“It meant being an accountant, being a successful businessman—anything that will provide you financial stability,” she said.

Originally, graduating college made her feel like she had achieved the American dream. Since then, her dream has grown bigger.

“Over time, it has evolved to making us feel we own this place. We are part of the American fabric,” she said. “The position I’m in now—I didn’t think that it would happen.”

She compared it to the feeling one might have sending a daughter off into a new marriage.

“I feel like the Korean American community has really married me off to the mainstream community. They want me to succeed in Congress.”

Kim has been involved in local politics for decades. Now that she’s in Washington, she might not be able to attend every Korean American event back home, she said, but she will be able to bring the immigrant perspective to the halls of the Capitol—and that is part of the American dream.

First and foremost, that likely means a focus on immigration itself. She knows from first-hand experience, and from her years helping constituents as a staffer for former Rep. Ed Royce, what it’s like to have to wait years to become a citizen. She understands the difficulties that plague tight-knit families who want to visit America briefly for a wedding or a funeral.

Kim isn’t alone in that perspective—not even among the delegation of freshmen from Southern California. Her friend and fellow Korean American Republican Michelle Steel was elected from a nearby Orange County district. Along with Marilyn Strickland from Washington state, they’re the first three Korean American women ever elected to Congress.

“We’ve seen these different kinds of candidates that we haven’t had in the past break through the hyper-partisanship,” said Sam Oh, a vice president at the GOP campaign consultancy Targeted Victory, who worked with both Kim and Steel. “It’s a way to reach out to people who traditionally haven’t voted or haven’t voted Republican.”

Oh suggested that the push to recruit outsiders, which opened doors for business leaders and veterans, has also created opportunity for candidates from minority and immigrant backgrounds.

“The Republican Party has become more inclusive,” said Daniel Garza, president of the LIBRE Initiative, a GOP-leaning group that focuses on empowering Hispanics. “You’re at a point where these constituencies are defining electoral outcomes at the federal level. … Candidates are starting to listen to our priorities, not just those projected by white liberals onto us.”

It’s the sort of message that seemed ascendant in the GOP in the years before President Trump took over: that the party’s future success would depend on winning over voters of color. The focus on minority voters in the Georgia Senate runoffs, as well as the gains the GOP made in immigrant neighborhoods in November, lend credence to that theory. At the same time, many GOP lawmakers avoid heavily focusing on their own identities.

“I don’t consider myself a Mexican American; I consider myself an American,” said Rep. Mike Garcia in an interview with National Journal. “There are too many teams within the team.”

Even eight months after taking office in a special election, the California Republican said he still finds himself waking up at 2 or 3 a.m. marveling at how surreal it is. But he said he still feels like the honor most representative of his own American dream was the opportunity he had to serve as a Navy pilot, an achievement he said was built on 15 years of hard work.

Garcia did mention his lower-middle-class background and his father, a Mexican immigrant who worked in construction. “I sometimes think tougher childhoods do help us appreciate the finer things when we accomplish them,” he said.

Some members who weren’t born in the United States exemplify how, even in times of national crisis, the immigrant view of America tends to be more optimistic than cynical.

“That is an opportunity a lot of Americans don’t value right now,” said freshman Rep. Victoria Spartz, speaking about the chance she says everyone has to pursue happiness in the United States. “We can complain about a lot of things, and we have some challenges and we can work through them. But we are still the greatest country in the world.”

The Indiana Republican arrived in the United States with one suitcase at the turn of the century. Since then, she has become a CPA, a business owner, and now, a member of Congress.

Spartz joked that most people’s dream probably isn’t to end up in politics, and she doesn’t blame them. But stories such as hers do illustrate her belief that Americans can achieve whatever they want in a way that isn’t possible elsewhere.

“In a lot of countries, if you’re not born in a wealthy family, if you’re not well-connected, you don’t have that opportunity,” she said. “If you work hard and ask people for help, people will help you. I didn’t have parents here. I didn’t have anyone here.”

Spartz grew up in Soviet Ukraine, making her an ideal messenger for Republicans’ crusade against socialism, which they argue has infected the Democratic Party.

“Many new GOP House members know exactly [what] it’s like to choose between freedom and socialism,” wrote National Republican Congressional Committee spokeswoman Torunn Sinclair in a statement to National Journal. “Their voices will be crucial as House Democrats continue to push an insane socialist agenda on the American people.”

But until the next election, the GOP will have to find ways to influence a Capitol Hill controlled by Democrats. Members from immigrant backgrounds are well-equipped for that, too.

Republicans who spoke to National Journal stressed the importance of bipartisan solutions, emphasizing economic issues, COVID relief, and educational opportunities.

Spartz talked about the need for more affordable health care options, especially for people who might want to leave their jobs to start businesses but are concerned about the insurance implications. Garcia said he wanted to push back on California’s high tax rates.

Garza mentioned criminal-justice reform—an effort to give people second chances—as an area that could see movement.

“America is still that country that awards hard work and perseverance,” he said. “At least I think it is.”